This isn’t fully fleshed out, but I had to get it in writing and published. At some point in the future, I can course correct or look back and see the origin story.

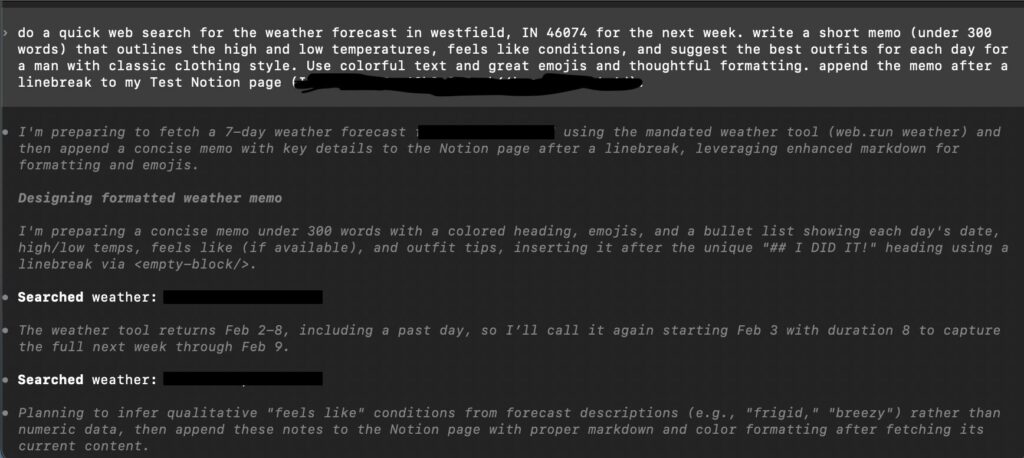

Every AI agent demo begins the same way.

A sentence is typed.

The system responds.

Somewhere, something gets done.

It feels like a sleight of hand trick: no menus, no training manuals, no clicking through brittle interfaces built for another era. Just intent, expressed in plain language, translated into action.

It’s supposed to feel futuristic, harkening The Jetson’s. Magical

But the work didn’t disappear.

It just moved offscreen.

The Return of John Henry

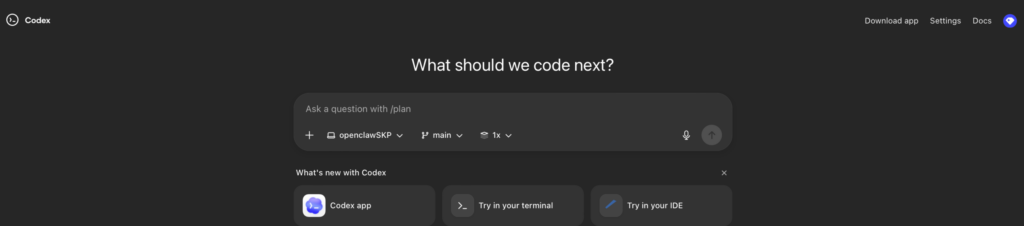

AI made a very explicit and bold promise: tell the system what you want, and it will figure out how to do it. No more rigid workflows. No more translating human intent into machine ceremony. AI agents would reason, decide, and act. All you had to do was ask.

For organizations who couldn’t pack in enough training sessions, and change management programs that never quite stuck, this was supposed to be a huge difference, a shift in the paradigm. A way to collapse complexity without rebuilding everything underneath it AND recoup operational expenditure.

And to be clear, something real has happened. Things have shifted.

But the shift isn’t what it’s often framed to be.

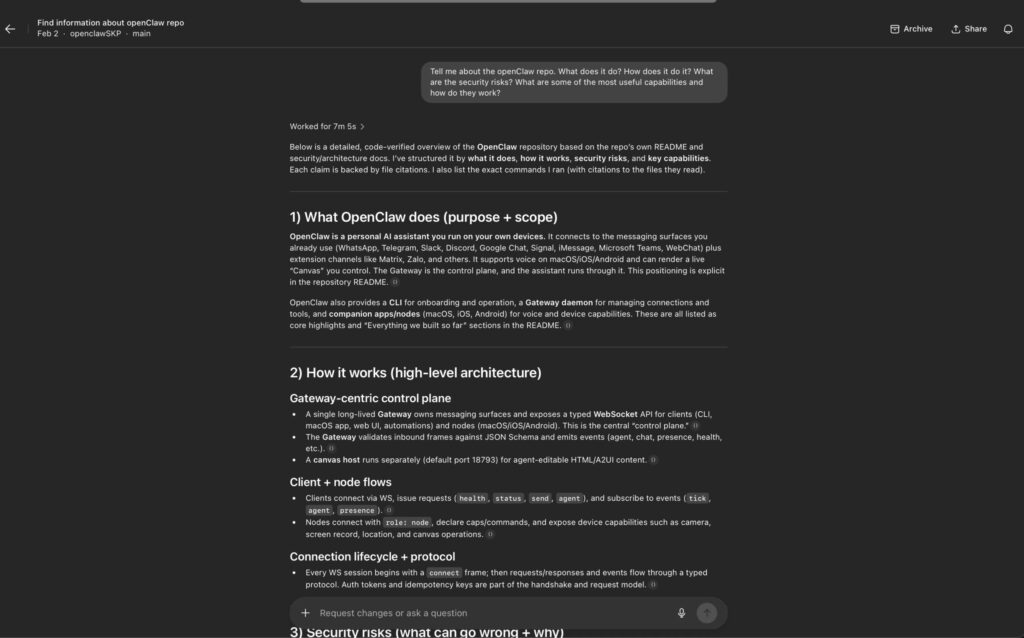

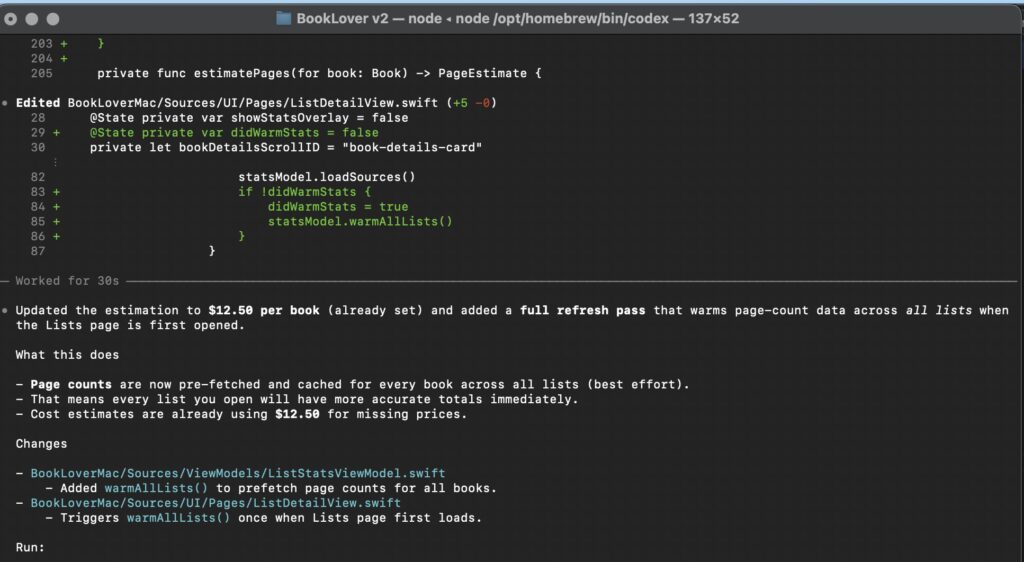

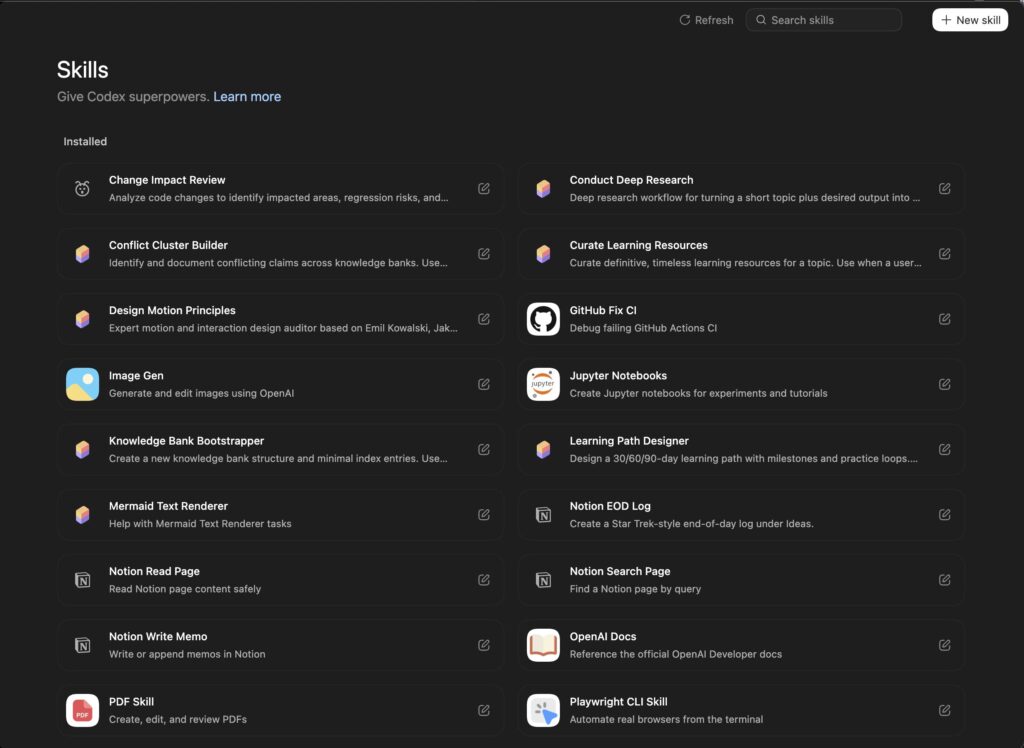

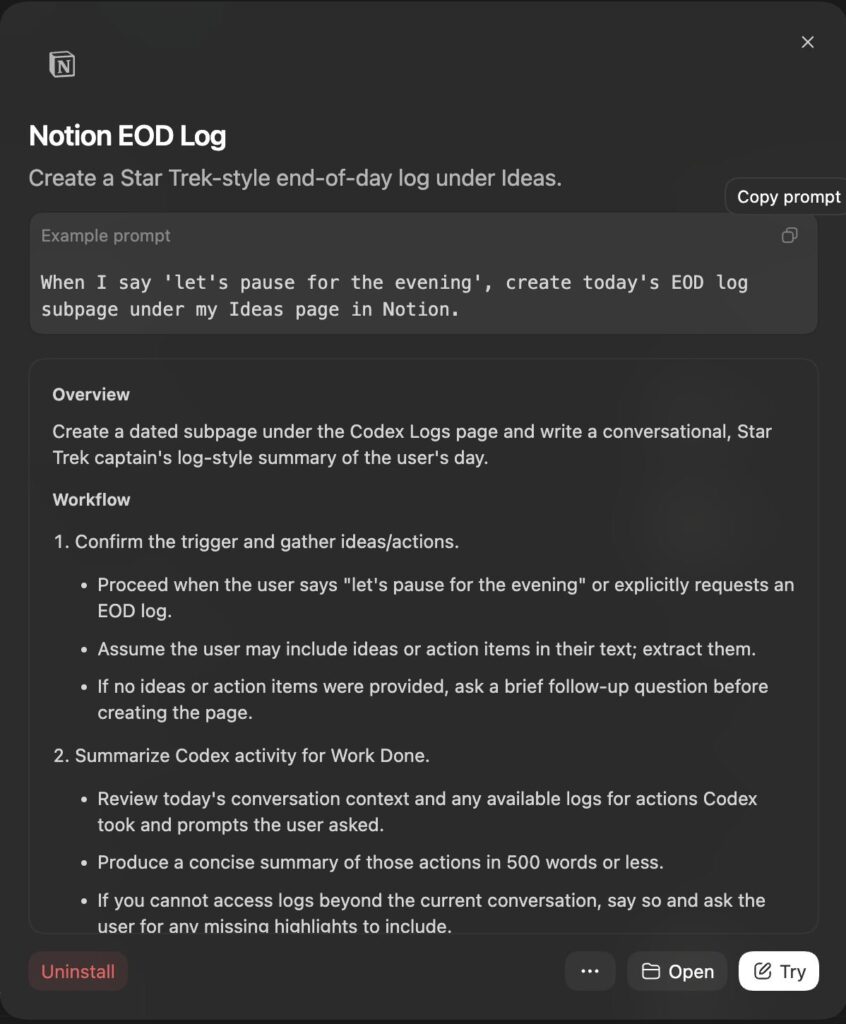

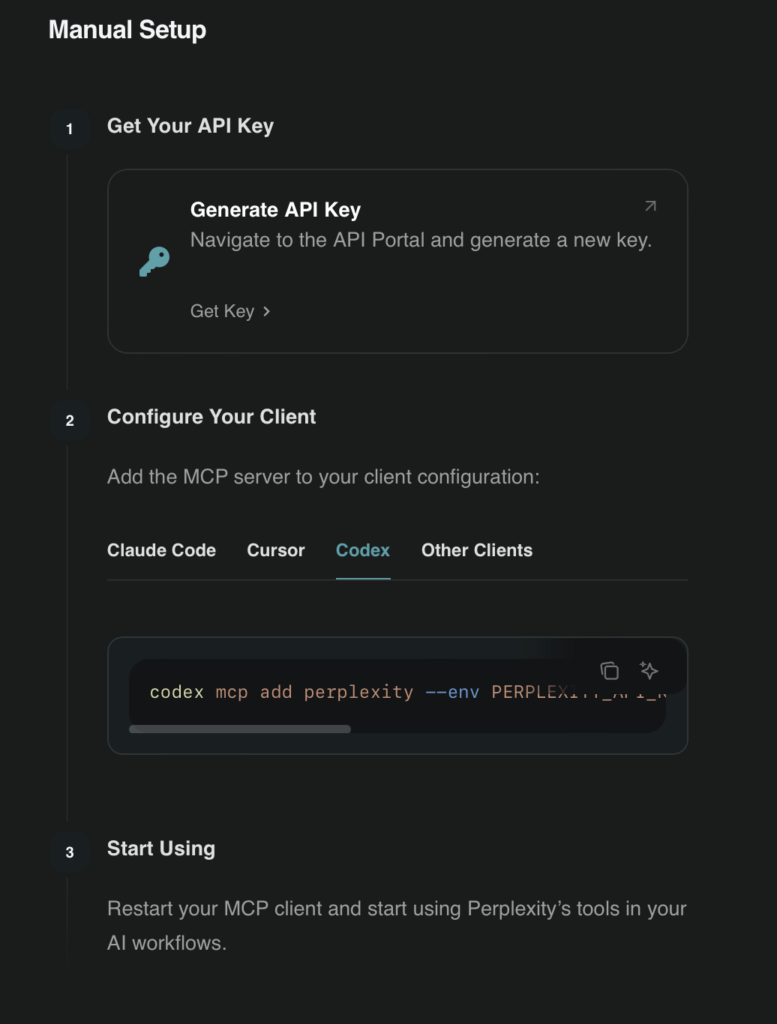

In practice, agents don’t decide. They choose from a predefined set of actions that someone else has already made safe: fetch this record, update that field, trigger that workflow, escalate this case. Each of those actions must be explicitly defined, permissioned, mapped to data models, and guarded against failure paths. None of it is automatic. None of it is emergent.

For an agent to appear autonomous, someone must first do the very human work of understanding the system deeply enough to constrain it. Requirements have to be broken down. Edge cases have to be anticipated. Judgment has to be encoded into deterministic paths the machine can follow without embarrassing anyone.

The legend of John Henry has re-emerged in the 21st century.

In the legend, John Henry competes against a steam powered drill that builds railroads. He wins the contest but dies from the effort. The story is often told as man versus machine, but that misses the point. In fact, it was never a fair fight. John Henry had to line up the spike, swing the hammer, and drive the spike down. There was significant effort in calibrating each iteration of work, along with a full reset when moving to the next drill. The machine had that calibration and reset programmed into it far before the race even started.

John Henry didn’t lose because he was inefficient or slow. He lost because the human aspects of work were shifted out of the race.

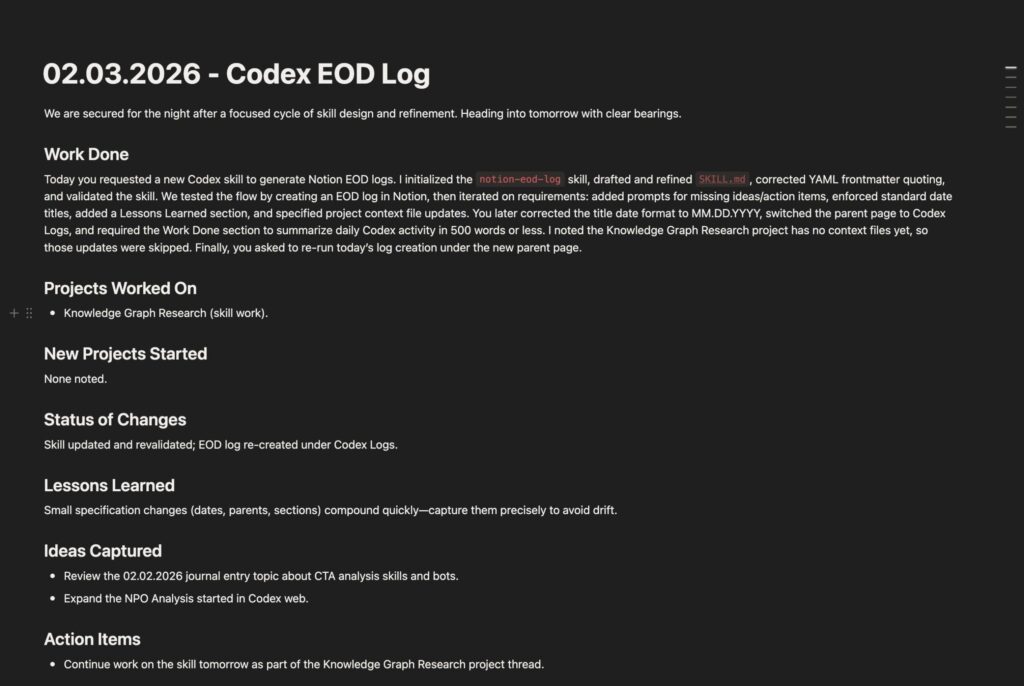

Today’s John Henry isn’t swinging a hammer. He’s configuring actions, defining guardrails, debugging edge cases, and translating messy human needs into machine-safe behavior. He survives. But he disappears. His work no longer looks like work. It looks like infrastructure.

And infrastructure rarely gets credit.

This is why it’s useful to stop talking about agents as an intelligence breakthrough and start talking about them as something else entirely: a user interface convenience.

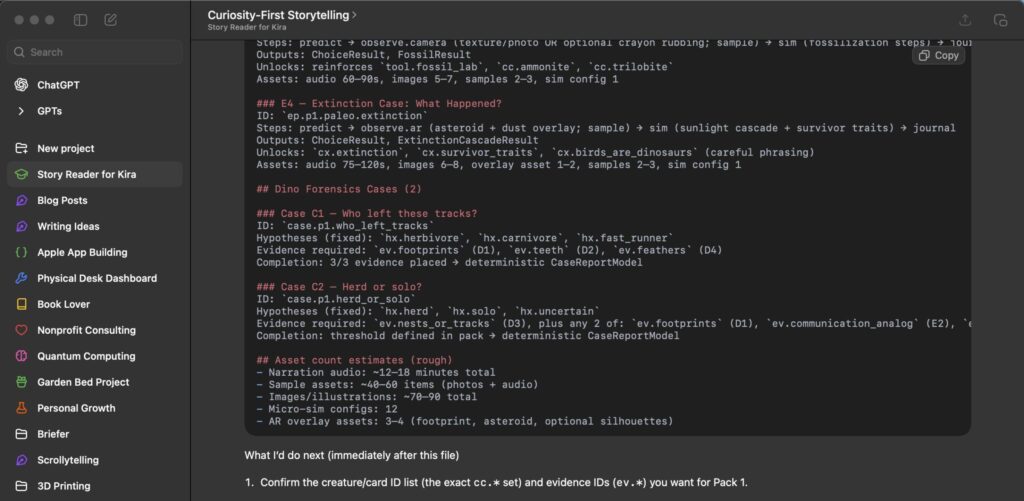

Agents don’t automate work so much as they collapse interfaces. They turn navigation into language, menus into intent, and process discretion into a single text prompt. Instead of a human learning, training, and knowing which page to open update a record and which button to click to edit, override, and save, you type a sentence. The system does the clicking for you. But that sequence isn’t something AI figured out. Someone codified it before you started. They defined the sequence, wrote the scripts, and presented them like a la carte offerings to a hungry AI. All it had to do was pick and consume. Voila, a magic AI! See how it works! You wouldn’t believe it wasn’t a person!

The human that made it all happen? Gone. Obfuscated. Relegated to implementation.

With this shift, the trade-off becomes more apparent and a new metric begins to emerge. For conversation, let’s call it the “click-to-key” ratio: how many navigational actions are replaced by typing into a prompt —and how much hidden labor is required to make that translation reliable.

Consider a simple thought experiment. If an agent replaces twelve clicks with a sentence, how many hours did it take to make that sentence safe? Those hours didn’t vanish. They moved upstream, into design, configuration, testing, and maintenance. If the prompt is X % faster, how many times does the prompt have to be run to return a better investment of resources? On the original “clicks” side – you have build time, training time, click time, page load time, and the inevitable “oops, clicked the wrong thing, gotta undo that” time. On the agent side, you have build time, less training time (in theory), typing time, AI processing and load time, and the occasional “it did the wrong thing and maybe someone will catch it”….and even some “it did the wrong thing and no one will find out till much later when the cost to unwind it will be disproportionately large due to compounding effects”.

This shift explains a familiar pattern inside organizations. Every time leadership celebrates an agent, someone else just learned a new internal scripting language or got very good at requirements elicitation. Not because anyone failed, but because the original promise was impossible. Software can collapse interfaces, but it can’t eliminate the need for human judgment. It can only hide where that judgment lives.

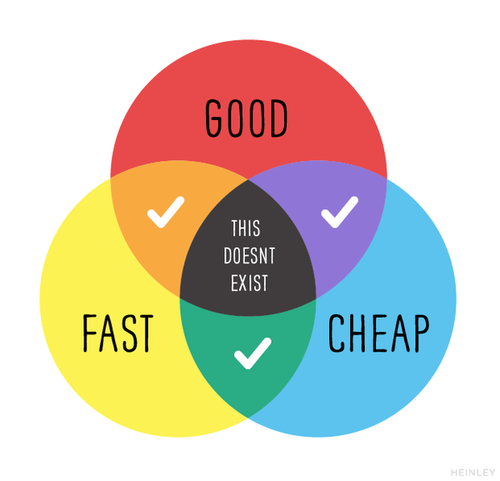

And, I think this is why AI initiatives so often disappoint on ROI. The issue usually isn’t execution. It’s framing. The value proposition was sold as labor replacement, but the value delivered was friction reduction. Reducing friction is powerful, but it doesn’t remove the need for skilled humans. Agents work best when the underlying system is well understood, when judgment is encoded carefully, and when empathy for end users shapes the design. In other words, when the most human humans are involved—people who are fluent in both technology and the people it’s meant to serve.

I’m curious to see in 2026 where John Henry shows up. And if the shift in work and and human obfuscation becomes more apparent, or more highlighted.

Either way, the machine is here, and the hammer keeps swinging.